The Noises hold a very special interest for seabird lovers. Being home to at least…

We need to talk about kina

The number of living creatures of all Orders, whose existence intimately depends on the kelp, is wonderful… I can only compare these great aquatic forests of the southern hemisphere with the terrestrial ones in the intertropical regions. Yet if in any country a forest was destroyed, I do not believe nearly so many species of animals would perish as would here, from the destruction of the kelp. – Charles Darwin, The Voyage of the Beagle

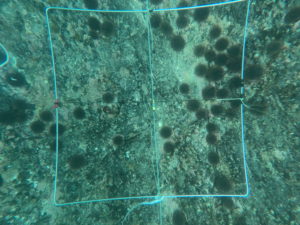

If you’re a keen snorkeller, you’ve probably noticed that over the years, the ocean has changed significantly and, one change that is especially hard to ignore is the proliferation of kina barrens (Evechinus chloroticus) around rocky reefs in the northeastern reaches of New Zealand. These spikey echinoderms no longer nestle discreetly in lush swaying kelp Ecklonia radiata), today they’re just as likely to be found congregating on barren rocks, like a prickly polka-dot quilt spread upon the seabed.

This marked increase is largely due to declines in important predatory species that feed on kina, notably tāmure/snapper and kōura/crayfish with the latter relying on healthy kelp forests for larval settlement and shelter. Pāua are also outcompeted where kina are abundant. Without their traditional predators, kina have been able to graze kelp forests to obliteration, literally eating themselves and many other species out of house and home and, without kelp forests to form the base of the food chain, all other reef species are threatened. Even if you’re a fan of eating kina, this abundance is no cause for celebration either because the roe of kina from a barren is small and skinny, with little nutritional value.

One response to this thorny problem could be to try to remove the kina, but removal on its own does not address the underlying problem. It’s also important to note, kina are a taonga species and play an important role in the ecosystem, and it’s only when there’s an excess that an imbalance is caused. Understandably, there has been a lot of community interest in the idea of removing kina. However, there are also cultural considerations and the practicality and long-term effectiveness of removing kina needs to be examined before such an approach can be adopted. This is why scientists from The University of Auckland proposed a project to work with mana whenua, the Neureuter whānau, matāwaka, rangatahi and marine scientists. Led by Assoc. Professor Nick Shears, alongside PhD student Kelsey Miller, the project’s aim is to test the viability of large scale kina removal and how it might be incorporated into wider plans to restore mauri to the Hauraki Gulf’s rocky reefs.

Following consultation with Ngāti Manuhiri, Ngāti Rehua and Ngāi Tai ki Tāmaki, the project is now underway across three locations and four sites at Leigh, Hauturu-o-Toi/Little Barrier, and Ōtata at The Noises. Now the prickly pillagers have been removed, the sites are being monitored regularly, using a framework that’s not dissimilar to terrestrial ecological work, where pest removal and regeneration help restore balance.

Naturally, we’ve been following the progress with interest, specifically at the Ōtata site, so to learn more, we spoke to PhD student Kelsey Miller.

Q. The Hauraki Gulf is vast, how did the team choose the removal sites?

A. We picked sites with varying conditions to figure out when and where removal can lead to restoration. Closer to Auckland there is more sedimentation, less water clarity, whereas towards Leigh, and at the offshore islands, there’s better water quality, less sedimentation, and much more wave exposure. The project is less about trying to restore these specific sites and more about trying to determine how and where kina removals can be a useful tool in promoting kelp recovery.

Q. How did you do determine the size of the test areas?

A. We knew we had to make them pretty substantial, so the Ōtata site is just under two hectares and although it’s a large area to clear, it represents only a very small area of rocky reef and a fraction of the total area of Ōtata’s kina barrens. We also knew from Nick’s previous experiments, as well as urchin removal worldwide, if the area is too small kina will return quickly because they are mobile. So the plots had to be large enough to be mostly self-sustaining, rather than requiring us to go back on a regular basis to continuously remove kina, which you’d have to do for smaller sites. The larger the area kina are removed from, the more resilient it will be to potential reinvasion, which is inevitable unless kina numbers are continuously controlled, or other protection measures are put in place.

Q. Is it expensive, this sort of operation?

A. We are very fortunate to have funding from G.I.F.T. to support this research and the main cost in kina removal as a restoration tool is simply the time and effort involved in manually removing kina from large areas of reef – it is very labour intensive, particularly at meaningful scales. Our research has largely been undertaken by scientific divers from the University of Auckland, including staff, students and volunteers. However, there is a lot of community interest in this research, so if kina removals are proven to be a viable tool, then community input would be one way of reducing costs. But, that would require clear protocols and appropriate permitting from MPI, as well as engagement with mana whenua. We are definitely not encouraging people to start removing kina on their own.

Q. How did you remove the kina?

A. The first step of our project involved getting an MPI Special Permit which allowed us to trial a range of removal methods including collecting or culling kina, either on scuba or by freediving. In consultation with mana whenua and MPI, we then decided which method was the most appropriate for the purposes of this project. One of biggest problems with kina in barrens is that they’re quite starved so not as good for food as those from kelpy reefs. As a result, collecting large volumes, tonnes, of skinny kina was not practical and they’d ultimately need to be disposed of on land. While there are possible opportunities to be explored for utilising kina from barrens, the most practical and efficient method was culling, by simply breaking the kina open underwater. This way too, their remains stay within the marine system and it was also very rewarding to see dozens of different species of fish and invertebrates, including sea stars and octopus, feasting on the culled kina. It would’ve taken at least twice as long to collect the kina, and we didn’t have a way to deal with them on land. In this experiment, the number and estimated biomass of all kina removed were reported to MPI and are included as catch in the wider fishery. It’s also important to note that while culling was used for this particular experiment, in the future we would encourage alternative methods and exploration of different uses of kina from barrens.

Q. How deep is the Ōtata site?

A. It went down to the kelp line at about 10 metres. Kina barrens typically form within a distinct band, from the shallows to their preferred depth range, which is helpful from a restoration point of view, as there’s almost always kelp in deeper waters. This means there is a source population for new kelp to replenish the removal area. It was more efficient to do the removals on scuba, even at shallow depths it’s at least as twice as fast, and depends greatly on the skill of the freedivers. Several experienced freedivers worked in the shallower waters and they made a huge contribution.

Q. How long did it take, and how many of you took part?

A. It took roughly 150 hours of dive time at Ōtata, and this was similar to the other removal sites. Across the whole project, more than 50 people were involved. It takes a lot of effort to remove kina from a relatively small area, which further highlights the need for the protection of kina predators, like tāmure and kōura, so balance is restored to the ecosystem.

Q. And the timeline?

A. We carried out initial surveys at Ōtata in November and December of 2020 and did the kina removal from January 15 to February 4. We’ll keep monitoring kelp regeneration every six months for the next two years, as well as looking at roe quality of the remaining kina.

Q. How’s it looking so far?

A. We did our six month resurvey at Ōtata on Wednesday [August 4, 2021], and kina densities have stayed low in the removal area. There are a few baby kelps coming in, although not as much compared to earlier sites at Leigh. However, those sites were completed earlier and Ōtata hasn’t yet had its main growing seasons which are spring and summer. But there is a huge amount of juvenile Sargassum sinclairii, a fucoid kelp species, coming in, and just because we haven’t seen major kelp growth, it doesn’t mean we won’t, as we’ve yet to see a summer following removals. Of all sites, higher sediment and lower water clarity were expected to be more challenging on Ōtata, with less recovery, but it’s still exciting to see Sargassum, as well as other species. Over some of the quadrats, which are 1m square, there are up to 80 little baby Sargassum and some Carpophyllum coming in. Kina numbers remain high and there is no sign of any change at the adjacent control sites where kina were not removed.

Q. What are the cultural sensitives, in relation to this trial?

A. There are several community kina removal projects going on. Waiheke is doing theirs within recreational bag limits. However, for us to undertake this larger-scale research, we needed a special permit from MPI, which required considerable engagement and consultation with mana whenua. There were meetings, and we got letters of support because there has to be sensitivity with this scale of removal of a taonga species. We didn’t take that lightly and it was also very exciting for us to have a clause that allowed us to donate some kina when the quality was good. We don’t like to see it being wasted, and to our knowledge, this is the first time that’s happened. We’re also hoping, that the remaining kina improve in condition and size, with better, bigger roe, and better value as kaimoana.

Q. How is success measured?

A. Firstly we’ll compare the area, density and biomass of kelp in restored vs control reefs. Secondly, we’ll note changes in the size and condition – relative gonad weight – as it is expected there’ll be increased size and quality through the restoration of kelp forests. And thirdly we’ll investigate how other ecologically important kaimoana species respond – if there is a rise in reef fish and crayfish numbers. By following the removal areas over a longer time frame we will also be able to examine how long it takes for kina to repopulate and ultimately return to the sites, which is inevitable unless kina numbers are continually controlled or other wider protection measures are put in place, once again emphasising that kina removal is not a solution on its own.

Q. What have you seen from similar studies overseas?

A. First indications from kina removals worldwide are that they generally allow kelp to come back pretty quickly in the order of around 18 months. And it’s a simple, relatively cheap method that can restore an ecosystem although it won’t bring back crayfish and other important predators that ultimately control kina numbers. That will only happen when there is less fishing, so reducing kina numbers can’t be seen as a solution on its own. We hope to figure out how useful it is as a tool and how it can be combined with other longer-term solutions – like co-management, predator protection, kina harvest – to best restore mauri to the Hauraki Gulf.

After two years when the experiment is complete, the results will be shared online, at conferences, published in scientific journals as well as made available at the Goat Island Marine Discovery Centre. The project also hopes to provide a model to promote, guide, and focus restoration efforts across wider areas of the Hauraki Gulf and throughout New Zealand and you’ll also be able to read about progress here on this website.

This study was funded in part thanks to a grant from G.I.F.T., and would not have been possible without all of the volunteers and partnerships.